February 2021

February 2021

After years of lacklustre performance and miscues, Condominium Authority of Ontario (CAO) is receiving a higher level of scrutiny by the Auditor General who utilized her office, resources and influence to better identify issues that have become apparent and reported on by Toronto Condo News in the three years since it was established.

In her annual report to the legislature, Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk suggests that Ontario needs better oversight of the condominium industry and states “The existing legislative model for the condo sector does not address the risks that exist for condo owners and buyers”. Value-for-Money Audit: Condominium Oversight in Ontario (2020) is the Auditor General’s nearly 80-page report detailing findings. According to the report, the existing model for the condo sector does not provide effective consumer protection and fails to address risks that exist for condo owners and buyers.

The Auditor General notes that many reforms expected to take place have yet to be implemented.

Regulatory Overview

Condominium Authority of Ontario (CAO), including Condominium Authority Tribunal (CAT), and Condominium Management Regulatory Authority of Ontario (CMRAO) were created in 2017 to provide oversight of the condominium sector. The CAO is self-funded through mandated fees to all condo owners. It is a not-for-profit corporation designated as an administrative authority under the Condominium Act, 1998, and overseen by a seven-member board of directors; four of whom resigned in 2020 citing “recent conflict of interest and governance concerns”.

Condominium Authority of Ontario (CAO), including Condominium Authority Tribunal (CAT), and Condominium Management Regulatory Authority of Ontario (CMRAO) were created in 2017 to provide oversight of the condominium sector. The CAO is self-funded through mandated fees to all condo owners. It is a not-for-profit corporation designated as an administrative authority under the Condominium Act, 1998, and overseen by a seven-member board of directors; four of whom resigned in 2020 citing “recent conflict of interest and governance concerns”.

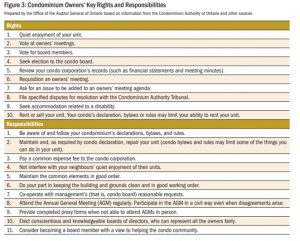

The CAO has limited jurisdiction over the matters it can handle. This results in condo owners and purchasers being unable to resolve many of their condo-living issues efficiently and cost-effectively.

The CAO’s mandate under the Condo Act is limited “compared with the mandates given to other administrative authorities in Ontario. These limitations provide weaker protections for condo owners.” The CAO mandate does not permit them to 1) inspect or investigate potential abuses or misconduct by condo boards or individual directors; 2) investigate non-compliance with the Act, the regulations, or a particular condo’s declaration, bylaws, rules or policies; 3) enforce the Act and regulations except in very limited cases; or 4) get involved with board-related matters such as elections in condo corporations and financial management of condo corporations.

The CAO requires authority from the Ministry of Government and Consumer Services (Ministry) prior to expanding its services. CAO has indicated it agrees with or will review many of the Auditor’s recommendations.

According to the Ministry “other administrative authorities regulate providers of services to the public and that providing such powers to the Condo Authority would go against the principle of self-regulation for condo owners.” Increasing CAO authority “could have a significant impact on the principle of condo self-governance, and has implications regarding the extent to which the government, or a regulatory body, could potentially become involved in the decisions made about the management of homes or other private property (including common areas collectively owned by condo owners).”

The Ministry agrees with the Auditor’s recommendation to “undertake an analysis of having a single condo authority and a standalone Condominium Authority Tribunal (Tribunal)” that could eliminate the need for a separate CMRAO.

Market Overview

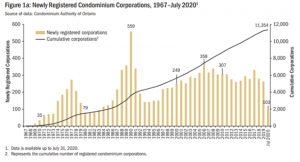

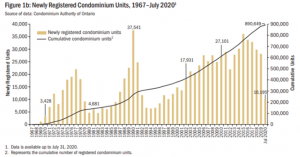

There are approximately 890,000 Ontario condo units in buildings managed by 11,350 condo corporations.

According to Statistics Canada 2018 data, 86 percent of all Ontario condominiums are owned by individuals. Only 57 percent are owner-occupied.

Findings of the Auditor General

General

The Auditor noted that CAO, CMRAO or the Ministry were not collecting sufficient information to allow them to understand the sector. The Auditor General conducted two surveys – one of condo owners and another of condo boards – while preparing the report.

Ministry enforcement powers were found to be weak and used infrequently, and “the government has not prosecuted an individual or corporation for an offence under the Act in the last 10 years.”

Condominium Authority of Ontario

Condominium Authority of Ontario “lacks the ability to inspect or investigate potential abuses or misconduct by condo boards, or investigate non-compliance and enforce compliance with the relevant legislation and regulations.”

The Auditor found that “the public registry maintained by the Condo Authority does not readily serve the needs of the condo community by providing accurate, complete and useful information.”

Condo Boards, Directors and Elections

The CAO lacks the ability to inspect or investigate potential abuse or misconduct by condo boards, or to investigate and/or enforce compliance with the condo legislation. They are unable to get involved in the challenges of effective board governance, such as ensuring sound elections to the board and effective financial management of the corporation.

Over 6,000 ineligible condo directors (17 percent of all directors) serve on condo boards despite not having completed director online training. Less than half were advised by the CAO of their disqualification. The Ministry denied a request by CAO to allow it to post the ineligibility of these individuals on its public registry. The Ministry “sent a letter to the Condo Authority in January 2020 instructing it to discontinue notifying ineligible directors or their condo boards of their disqualification, as the government had not delegated this responsibility to the Condo Authority.”

Mandatory director training is comprised of 21 educational modules expected to take between three and six hours to complete. In practice, this can be done without reading the materials. Over half the directors completing training took between 0 to 10 minutes to complete the majority of individual topics which can be done by clicking through all topics without reading them. Approximately seven percent took less than an hour to complete the entire 21-module program.

Information on the interests of directors who serve on multiple condo boards is not transparent. Over 1,000 directors were found to have served on multiple condo boards with some serving on up to 30 boards. This represents 19 percent of all condo corporations, and 24 percent of all condo units, registered in Ontario. Of boards surveyed, 95 directors were found to serve on the board of at least five different condominium corporations. In 15 out of 20 condo boards sampled by the Auditor, the presence of directors with commercial interests made up a majority of the board. This may or may not be problematic or a conflict of interest depending on their actions and voting at board meetings. A majority of those found to have commercial interests were identified as “real estate development, ownership and management”.

About 20 percent of condo boards report insufficient directors to achieve quorum.

Condominium Authority Tribunal (CAT)

The CAT is responsible for carrying out dispute resolution online. Its objective, to provide quick and inexpensive dispute adjudication, was found to be too limited and only able to hear about 11 percent of all of condo disputes that have been adjudicated by our provincial courts in the last 50 years.

“Condo owners who face common issues or are involved in disputes either with their boards or with other owners in their condos are largely left still unable to resolve most of their issues in a timely and cost-effective manner.”

“Condo owners are not on a level playing field with condo boards at the Tribunal.” In appearances of cases heard by the Condominium Authority Tribunal, condo owners were self-represented 84 percent of the time. Corporations were represented by a lawyer 91 percent of the time. To make the playing field between condo management and residents more level, the report suggests lawyers be moved outside the equation as in British Columbia.

In short, “an effective dispute resolution process for these significant challenges has yet to be established.”

New Condo Communities

Legally, developers are required to provide new condo buyers with a budget estimating common expenses and fees for the first year. Developers fail to budget sufficiently for reserve funds requiring condo owners to make unexpected and significantly higher payments to compensate. They fail to provide purchasers with a reasonable estimate of condo fees. Maintenance costs may be omitted, understated or deferred to subsequent years. Most condo corporations end up increasing reserve fund contributions by an average of 50 percent. On examination of second-year audited financial statements compared with the developers’ budget statements for a number of condo corporations registered in 2016, the majority indicated an average increase of 77 percent in their condo fees compared with the developers’ budget. Only one registered a decrease.

The survey of condo owners “found developer-set condo fees increased as much as 30 percent in the first two years after the condo’s registration, and as much as 50 percent in the five years prior”.

In British Columbia, developers understating expenses pay a penalty – twice the amount if expenses are less than 10 percent more than the budget statement, and three times the amount if the discrepancy is at least 20 percent.

Reserve Funds and Reserve Fund Studies

The Auditor found that regulations relating to reserve funds do not require condo corporations’ reserve fund studies to budget for necessary major repairs beyond 30 years at any point in time. It was noted that many expensive items like boilers, windows and building cladding may only require replacement 40 to 50 years after construction, and that condo boards “often do not budget for them in the first 10–20 years”.

A review of reserve fund studies found that 69 percent had inadequate amounts set aside and higher contribution amounts averaging 50 percent being necessary. The Auditor relied on reserve fund experts who note that “increasing the budget window to 45 to 60 years … will allow the cost of maintaining the condo building to be spread more equitably for both current and future owners of the condo building’s units.”

Of condo boards surveyed, 29 percent reported raising funds through special assessments within the last five years.

The Auditor has recommended to “extend reserve fund studies of condo buildings to include the cost of repairs and replacements looking forward 45 to 60 years, instead of 30 years.”

Condo Management Regulatory Authority of Ontario (CMRAO)

Despite it being illegal to do so, hundreds of unlicensed individuals and companies provide condo management services. The CAO’s public registry was found to include 316 individuals and 156 companies that provide unlicensed management services. Of this group, 38 percent were found to be advertising themselves as providing property management services.

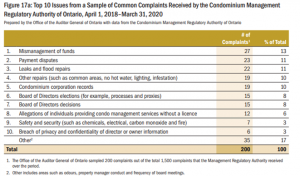

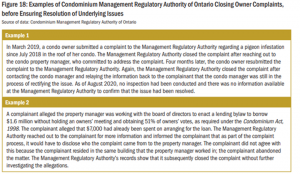

This oversight body for condominium managers did not effectively address nearly half of the complaints sampled. It did not proactively exercise its authority to inspect condominium managers and management companies.

The CMRAO took limited action on nearly half of owner’s complaints sampled by the Auditor. Inspection efforts were found to be mainly reactive. They failed to establish targets to assess its performance of most of its mandate activities.

The Auditor’s final conclusion is that mandates given to the CAO and CAT are limited and insufficiently protect owners against issues they encounter in daily condo living. The CAO was found to be lacking effective and efficient processes and systems in place to carry out its mandated responsibilities. CMRAO was found not to have put in place effective processes to resolve complaints against licensed condominium managers and management companies, and failed to conduct proactive inspections of licensed managers and companies.

Read Value-for-Money Audit: Condominium Oversight in Ontario (2020) – the Auditor General’s report detailing findings.

Read Value-for-Money Audit: Condominium Oversight in Ontario (2020) – the Auditor General’s report detailing findings.

Read the Auditor General’s report or any of the Value-for-Money Audits .

Its smart to ask for help

The Auditor General relied on and made mention of experts that provided advice and education while preparing the report. This remains a best practice condo boards are encouraged to emulate.

The Auditor General relied on and made mention of experts that provided advice and education while preparing the report. This remains a best practice condo boards are encouraged to emulate.

Specialized expertise includes engineers, lawyers and accountants.

Condo consultants, such as CondoHive (www.condohive.ca), offer a more comprehensive understanding of the priorities, issues and conflicts inherent in overseeing and running a condominium community. They can advise on best practices; strategy, implementation matters and incorporating recommendations from specialized consultants to avoid internal conflicts and poor decisions.